How to Write Act I: Opening Scenes for Your Fictional Story

Many writers come up with an idea for a great story but get stuck on the opening scenes.

* Where do you start?

* What should be included in chapter one?

* How should you introduce the characters and the story world?

* What exactly is an ‘inciting incident?’

* When do I insert backstory?

* What is Plot Point I?

In our post, How to Write Act I: Opening Scenes for Your Fictional Story, we answer each of these questions to help set your writing on the road to success.

ACT I: Story Openings

The opening scenes set up the entire story. If written well, the rest of the story should fall into place. If written poorly…the story could lose focus and fall apart.

Learning which elements belong in your opening scenes (or Act I of a 3-Act Structure story) can help you create stories faster with less frustration. Knowing what to include can also help you strengthen your stories so they may have more impact on your readers.

Follow along as we discuss:

1) Characters

2) Setting

3) Genre, Theme, & the Story Question

4) Pacing & Point of View

5) The First Scene

6) Inciting Incident

7) Plot Point I

1) Characters

- Who is the protagonist?

As the story opens, it is crucial to hook the reader’s emotions so that they feel connected to the characters and events of the story. You will likely want to begin the story in the protagonist’s POV. Start with an event or situation that piques interest and introduces the main character’s personality. Hint at the character’s strengths and possible weakness. Pick a scene that is going to best show who your character is.

Have your protagonist demonstrate an admirable quality, skill, or strength to create an immediate bond with the reader. Perhaps they have a unique or passionate viewpoint about a given situation. Give the reader someone likable who they can care about and root for.

Then afterward, perhaps in another scene, also give the reader a hint at this character’s weakness and the lesson this character may need to learn by the story’s end. What is this character not good at?

- Introduce the protagonist’s short-term goal and long-term goals. Show through the character’s actions what is important to him. What does your character WANT? And WHY? What is your character’s PLAN to achieve his goal?

- Introduce the conflict: Your main character should have both internal conflict (emotional conflict within himself) and external conflict (conflict with an outside force, either the environment or another person who opposes him). What problem must he/she overcome? Who or what will try to stop the protagonist from achieving his goal? What are the stakes? What does your character most FEAR?

If you are not sure who your main character should be:

This character will decide to pursue a goal in order to overcome a problem. This problem will threaten that character’s ordinary way of life and the character will not be at peace until it is resolved. This character will have the most to lose if they do not accomplish this goal. This character also has the biggest lesson to learn during the course of the story, creating a “character arc” or transformation of the character from who he was at the beginning of the story to who he is at the end.

Special Note: If you have a buddy or friendship story, or a romance, or story where it seems there are two or possibly even three main characters, there will still only be ONE who has the bigger role.

For extra help on developing characters, see 10 Questions to Ask When Creating Characters for Your Story

Who will oppose your main character?

Every story needs conflict to make it interesting for the reader to keep turning pages. The opposition can be a true villain or a friend, family member, neighbor, coworker, or romantic interest who will work to keep the main character from achieving their goal throughout the story.

- Why is it important that they oppose your main character?

- What does the opposition have to lose if they don’t win?

For extra help on developing antagonistic villains, see 5 Questions to Create Believable Villains

Is there a romantic love interest? Or another main sub-character? (Another significant character who is active throughout the story?)

The opening scenes (or first few chapters of a novel) also establish the main character’s relationship with others.

Example for Romance: How do the hero and heroine meet? Introduce them in a memorable way! Why are they attracted to each other—or not? What is the first thing they notice about each other? The second? What is the main issue that will both drive them together and later, drive them apart?

These questions are also for buddy stories, stories that focus on a group of characters, and other relationship stories, such as novels focusing on sisters, best friends, or stories with family.

What is this other character’s relationship to both the main character and the villain/antagonist?

How will this character help or hinder the main character?

2) Setting

The setting of a story is not only a place, but also reveals the time period, season, lighting, temperature, props, and time of day. The same setting may look one way to one character and another way to a different character according to their viewpoint.

The description of the setting may also help establish the genre, mood, tone, and general pacing of the story.

The main character (protagonist) should begin in his normal ordinary world.

The opening scenes/chapters in Act I set up the story and deliver the following information:

- Who? What? Why? Where? And When?

- Where does this story take place? What kind of story is it?

The uniqueness of the ‘story world’ should be brought to attention as well as a brief introduction to the rules, customs, and social norms of this society.

- What is the time period?

- Type of dress? Typical food? Type of businesses and style of homes?

- What is the daily routine?

- How does the character either fit in or stand out in this world?

- What is special or significant about this setting?

- What past events in this setting should the character know about?

- How will the setting impact the characters or the events of the story?

Special Note:

If magic is the norm in this story world or if animals can talk, or if your characters routinely fly to work in a spaceship, you need to establish that this is the ordinary way of things on the first few pages to “ground” the reader with what they should expect.

Example: If a mouse can talk like a human in the story, then this needs to be addressed. Can all the mice talk or just one? Why?

This is especially true if writing a Fantasy, Paranormal, or Speculative Fiction story. If there is an element of magic, who can use it? How? When? Why?

Are there dragons? Elves? An element of the supernatural?

Is there a specific legend about a person or place in this setting? Or is there a prophesy the people here all know and are expecting to come true?

If you are writing a historical, perhaps in the Wild West or during WWII, what is special about the landscape or people in this region or this time era? What stands out and has an impact on the main character? Is your character at peace with his setting or a ‘fish out of water?’

And if your setting is more familiar to the reader, pick out a few details that makes this setting in your story special or different for the main character. What is it about this place that they like or dislike and why? What about it stands out to the protagonist?

3) Genre, Theme, & the Story Question

- Genre:

A tense, action-oriented thriller or suspense story may start with a murder, to show the reader right away what type of story they are reading, while a lighthearted romance may start with a cute-meet scene of attraction between the romantic couple. A group of characters in a spaceship who are being pursued by others in another spaceship will instantly suggest this story is science fiction or futuristic.

The details of the setting, together with the events of the plot, and mood/tone of the scenes will all serve to reveal genre.

- Theme:

The opening scenes/chapters may contain subtle hints of the story’s theme. You may show a character who has specific opinions about love, marriage, trust, forgiveness, or working with others.

A negative viewpoint on such matters may suggest this character has a weakness that he must overcome by the story’s end. The story journey will test the character in these areas and give the character new insight.

Perhaps if the character could not forgive another in the beginning of the story, the events of the plot will change him, and he will be able to forgive by the story’s end. This forgiveness theme would be the basis for his ‘character arc,’ the lesson the character learns by going on the story journey.

- Story Question:

The beginning of your novel should set up a Story Question for the reader. This is the question that hooks the reader and keeps them reading pages to find the Story Answer which is revealed at the end. It also gives the story focus.

Will the characters overcome (the opposition) and achieve their (goal) by story’s end?

Will the two lovers work out their differences and finally commit to marriage?

Will the group of adventurers find the long, lost treasure?

Will the heroic band of elves, dwarves, and men defeat the bad guys?

Will the detectives solve the mystery?

The Story Question is often your story’s one-line pitch, only phrased as a question. It is what the reader will worry about the whole time they are reading your book.

4) Pacing & Point of View

The opening scenes & chapters will also establish the ‘norm’ for the way the writer will handle switching POV (point of view) throughout the story.

For instance, if you switch POV from hero to heroine, hero to heroine, hero to heroine, the reader will assume that this will be the pattern throughout the rest of the story. If you were to suddenly throw a different POV in there in the middle of the story, it would disorient the reader because another POV character had not been set up from the beginning.

You will also establish the pacing of the story by the number of pages you spend in each character’s POV and the typical length of each scene and chapter.

5) The First Scene

Act I sets up the entire story. This is why editors and agents require the first 3 chapters with a book proposal—to see if they think the story will work. There may be three to five chapters in Act I, depending on the overall length of the book, and all of the scenes within these chapters can be referred to as ‘opening scenes’ because they are all ‘set up’ scenes. These scenes contain all the information the reader needs before they get into the main body of the story in Act II.

However, the opening scenes should NOT contain a lot of backstory. (Do not tell the reader everything that happened in the character’s past.) Instead, open with something already happening or about to happen in the present timeline. Or open with a minor problem the protagonist is dealing with.

Only reveal small tidbits of information the reader absolutely needs to know RIGHT NOW in order to understand the present story. As a rule, keep all backstory out of Act I and only reveal a character’s past in small doses throughout the rest of the story as needed. Keep the opening scenes active, not passive. Do not bog down the opening with too many details or information, even when describing the setting.

Now let’s talk about the First Scene, the true Opening Scene.

- First lines: Creating the perfect first line of a story is an art. Draft at least 20 ideas or more before you settle on one. Study the first lines of multiple published novels for inspiration. Perhaps you will start with a line of dialogue, or the character’s opinion about the setting, another character, or life. Perhaps the first line will foreshadow events to come.

Whatever you do, make sure the first line grabs the reader and is interesting enough to entice the reader to read the next line. Do not start with a boring, ordinary sentence. However, don’t let yourself get hung up on crafting the first line either. You can always come back and change it later. When you are just starting to write, just move forward.

- The opening of the first scene introduces the protagonist in his ordinary world where he/she may be interacting with others and facing a minor problem that will be compounded, (or made worse) by the more serious problem at the Inciting Incident a few scenes or chapters later.

- The reader is introduced to the characters and the story world. Also ask: How can you use the opening scene to show the character’s personality or profession, strengths or special skills, dreams and goals and beliefs all at the same time? Always try to have the scene working on multiple levels, but do not cram so much into the opening that it loses focus. The most important goal is to draw in the reader.

- Last lines, Hooks: The opening scene should finish with a hook, that forms a question in the reader’s mind, so they keep reading to find out what happens next. Study the last lines of scenes and chapters in published novels to see how you might write a ‘zinger’ or intriguing last line that pulls the reader further into the story.

6) Inciting Incident

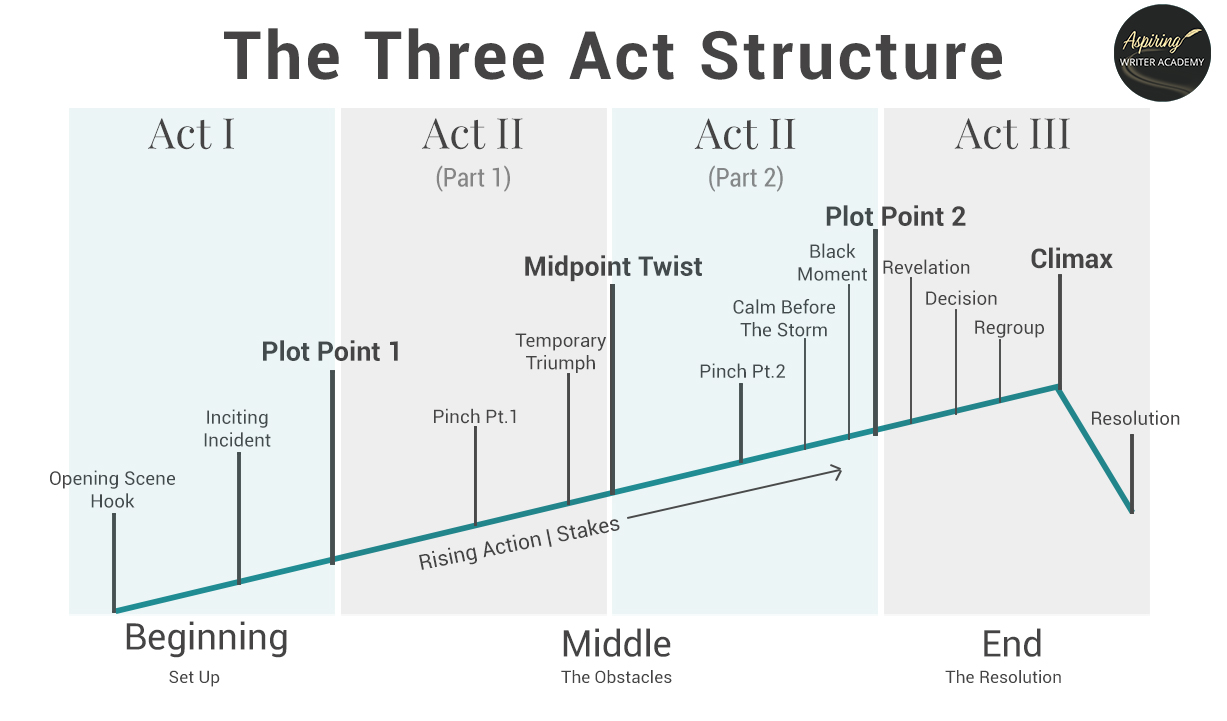

- Act I is short and usually only takes up the first 3 chapters, perhaps up to 5 chapters if writing a lengthy 100,000-word manuscript, less (perhaps only 2 chapters) if writing a short novella. About 2/3 of the way into ACT I, the protagonist should be faced with an Inciting Incident.

- This is not typically the opening scene problem or situation, but something far worse that the protagonist is presented with after the reader has already gotten to know him and the story world he lives in. First the reader has to care. If the inciting incident is presented too soon, the reader will not care what is happening to this character no matter how dire the circumstances.

- INCITING INCIDENT - (Story Hook, Catalyst, or Disaster #1): Something unexpected happens that turns your protagonist’s world upside down. He/she may get a phone call or letter with devastating news, or perhaps there is a murder or an accident. The protagonist is called upon to handle this problem which must be resolved.

- In many stories, it is the villain or antagonist of the story who delivers this Inciting Incident blow. It is the first major attack by the opposition against your protagonist.

- In an action-oriented story, or story involving a quest, this could also be the call to adventure, the opportunity to leave the ordinary world behind and do something new.

Example: An invitation (or command) to travel to an exotic location, journey into space, board the pirate ship on a quest for gold, join the wagon train on the Oregon Trail. Or perhaps the offer of a new job.

- The Inciting Incident should introduce serious conflict for the protagonist. The journey ahead will not be easy. And there must be a compelling reason why the character must What is at stake if the character does not go on the adventure or overcome this new threat to his way of life? This serious problem or goal motivates the protagonist and drives the story forward. The failure to solve this problem or achieve the new goal has life or death consequences either physically or emotionally or both.

- The character must then make a decision or decide upon a goal or course of action to overcome the Inciting Incident problem. The problem cannot be solved by another person, and it will not go away on its own. The consequences have to Life will never be comfortable again until the character does something to change the situation. Attempting to solve the problem or achieve the goal will force the character out of his comfort zone.

Example: In the movie, Romancing the Stone (1984), a reclusive novelist receives a ransom note demanding that she travel to Columbia to trade a treasure map for her kidnapped sister. The consequences: If she does not act, her sister will die.

- What is the problem the character must face?

- What are the stakes? What will happen if this character does not defeat the opposition, go on the quest, or solve the problem?

7) Plot Point I

PLOT POINT I - Answering the call to action. The character makes a decision on how to handle the problem he was just presented with during the inciting incident. At first the character may decline the offer or refuse to act. However, after considering the stakes, the compelling serious consequences, the character finds he must accept the call to adventure that takes him on the story journey. Even if it is the very last thing he/she wants to do.

- Plot Point I is the last scene of Act I. It is the actual decision to take action against the problem that will carry them through the rest of the book. It may be the specific agreement between two characters.

- In a romance, the hero and heroine are forced/or agree to work together or go on the quest together to defeat a common enemy or overcome a mutual problem. Or if they start out as enemies, it may be the vow to fight against each other over a specific issue (with a deadline) before they start to fall in love.

Example: Two people each determined to run for mayor. Only one will win by a certain date. Plot Pt. I would be their vow to run against each other for the position, which starts the upcoming battle. (The protagonist may feel he/she MUST win because of what happened at the Inciting Incident or their life and possibly the lives of the community will never be the same. Everyone will face dire consequences if the other opponent wins.)

- Plot Pt. I is the point where your main characters come together.

Example: Two cops, played by actors Mel Gibson and Danny Glover, become partners against crime in the movie Lethal Weapon despite their differences.

Example: In the movie, The Lord of The Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring, the hobbits, elves, men, and dwarves come together and form a group to travel to Mount Doom to destroy ‘the One Ring’ of power and defeat great evil.

- Your main character may have a strong-willed want or desire, or a personal goal he wants to achieve, and the conflict/problem the character was just presented with at the Inciting Incident will put that personal goal in jeopardy.

In response to this problem, the character must make a decision. The character comes up a story goal, with an action plan, to solve the big bad problem so he can get on with his life.

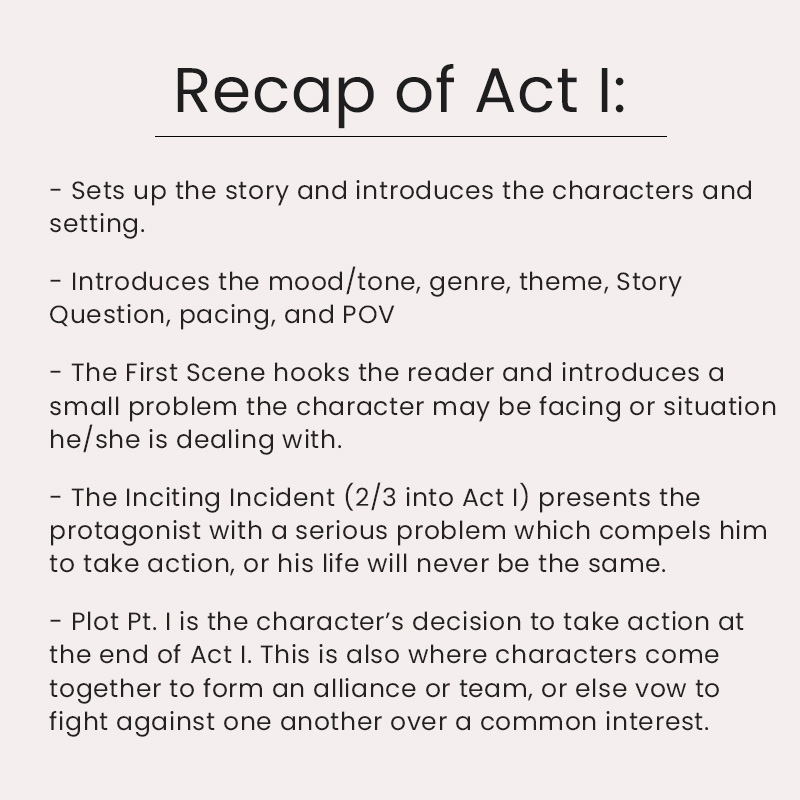

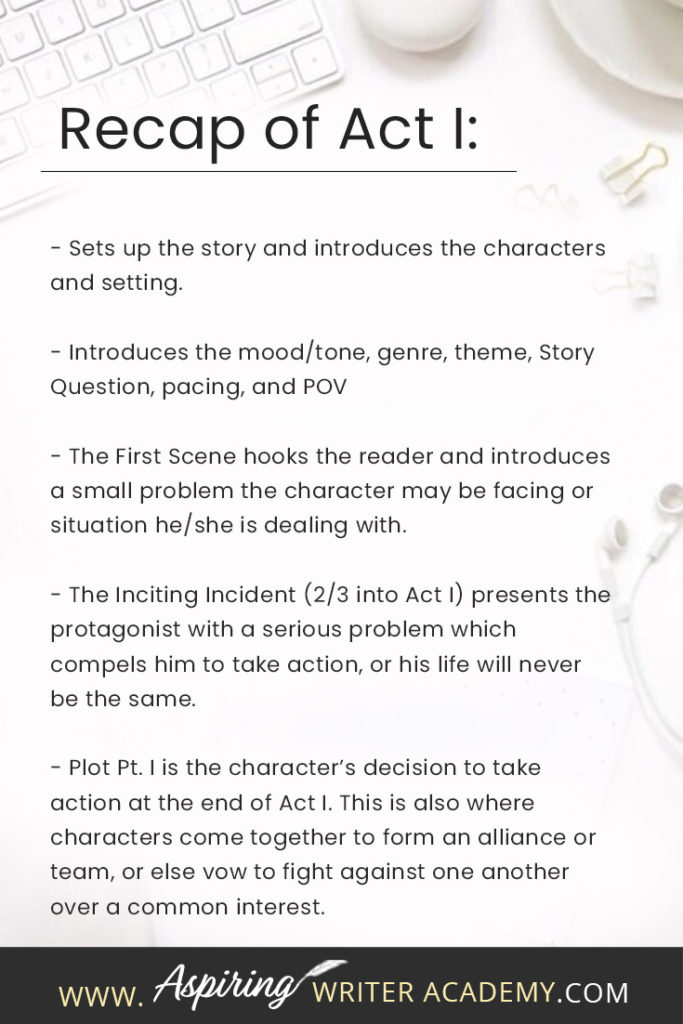

Recap of Act I:

- Sets up the story and introduces the characters and setting.

- Introduces the mood/tone, genre, theme, Story Question, pacing, and POV

- The First Scene hooks the reader and introduces a small problem the character may be facing or situation he/she is dealing with.

- The Inciting Incident (2/3 into Act I) presents the protagonist with a serious problem which compels him to take action, or his life will never be the same.

- Plot Pt. I is the character’s decision to take action at the end of Act I. This is also where characters come together to form an alliance or team, or else vow to fight against one another over a common interest.

We hope you have enjoyed How to Write Act I: Opening Scenes for Your Fictional Story have a better understanding of which elements should be included. The goal is to write a story that grabs the reader right from page one and convinces them to keep reading!

You may also want to download our free Brainstorming Your Story Idea Worksheet with fill-in-the-blank templates to help you further develop your characters and deepen your story.

Do you find it difficult to create compelling antagonists and villains for your stories? Do your villains feel cartoonish and unbelievable? Do they lack motivation or a specific game plan? Discover the secrets to crafting villains that will stick with your readers long after they finish your story, with our How to Create Antagonists & Villains Workbook.

This 32-page instructional workbook is packed with valuable fill-in-the-blank templates and practical advice to help you create memorable and effective antagonists and villains. Whether you're a seasoned writer or just starting out, this workbook will take your writing to the next level.

If you have any questions or would like to leave a comment below, we would love to hear from you!

Our Goal for Aspiring Writer Academy is to help people learn how to write quality fiction, teach them to publish and promote their work, and to give them the necessary tools to pursue a writing career.

ENTER YOUR EMAIL BELOW

TO GET YOUR FREE

"Brainstorming Your Story Idea Worksheet"

7 easy fill-in-the-blank pages,

+ 2 bonus pages filled with additional story examples.

A valuable tool to develop story plots again and again.

Other Blog Posts You May Like

Learn to Plot Fiction Writing Series: Story Analysis of “Beauty and the Beast”

How to Plot Your Fictional Novel (with Free Template Included)

The Ultimate Book Signing Checklist: What to Bring to Your First Book Signing

5 Questions to Create Believable Villains

Why Your Characters Need Story-Worthy Goals

3 Levels of Goal Setting for Fiction Writers

Fiction Writing: How to Write a Back Cover Blurb that Sells

Fiction Writing: How to Name Your Cast of Characters

How to Captivate Your Readers with Scene-Ending Hooks

Scene & Sequel: The Secret to Plotting an Epic Novel

Scene & Sequel: The Secret to Plotting an Epic Novel (Part 2)

Writing Fiction: How to Develop Your Story Premise

12 Quick Tips to Write Dazzling Dialogue

10 Questions to Ask When Creating Characters for Your Story

Macro Edits: Looking at Your Story as a Whole

Basic Story Structure: How to Plot in 6 Steps

is a multi-published author, speaker, and writing coach. She writes sweet contemporary, inspirational, and historical romance and loves teaching aspiring writers how to write quality fiction. Read her inspiring story of how she published her first book and launched a successful writing career.